U.N Talk

The Revolution Will Not Be Digitized ~ United Nations, March 2013

In March 2013, I had the extraordinary opportunity to address a delegation of international students from 40+ countries at the United Nations General Assembly in New York. The central focus of this year’s UNIS conference was how we approach the concept of change, from the micro to the macro, from the individual to the universal. In my talk, I addressed change from the vantage point of technological evolution – the nuanced interplay between the Ideas we conceive and the Tools we invent to bring those ideas to life. A condensed transcript below.

The Dawn of Man

One must open a talk on the evolution of Ideas and Tools with what is arguably the best portrayal of how man learned to think. Thank you Stanley Kubrick.

![]()

Somewhere way back in time, there was a primate who had a bright idea and changed the course of history from a world without tools to the world with tools. Imagine the magnitude of that shift.

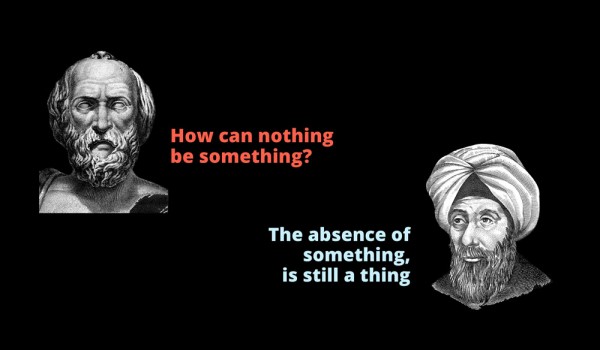

The History of Zero

Now jump ahead from the prehistoric era into to the 5th century AD, and explore another paradigm shifter – the invention of Zero. The number Zero is a universal concept today, but it came to be through centuries of discourse and debate between ancient Indians, Arabs and Greeks.

As far back as the 5th century, the Indians had a name for zero – they called it Pujyam/Shunya in sanskrit, meaning ‘The Void’ – after Brahma, the formless and limitless creator of the universe. See, the Indians were pretty comfortable with this notion that the “void” or emptiness can carry great value. When the Arabs learned of this, they embraced the idea as well. The Greeks, however, resisted it raising a very important philosophical question:

For the Greeks, this idea went against their cosmology as they believed in a finite universe. The notion of infinity and a limitless void carrying meaning was so unfathomable they tried to ban Zero for fear that it would challenge their religious order. It wasn’t until the 12th century that the ‘West’ finally embraced this idea that Nothing could be a symbolic placeholder for something yet to happen — that ‘nothing’ could be a connector, a divider, a differentiator of that which is to come. Zero lead to groundbreaking discoveries in the realm of mathematics, science and philosophy, fundamentally changing the ways we thought about Ideas themselves – in that something of value can actually come from nothing.

The Printing Press

Let’s move forward a few centuries, to the 15th century. By this point, Ideas have become a very hot commodity. The ruling powers everywhere knew how important and powerful Ideas could be. In the West in particular, the church and the monarch maintained a very strict control of knowledge, dictating what Ideas were passed on and taught to the masses. And almost all books were hand scribed in Latin by the church scribes and monks. And then came the invention of another tool – The Printing Press.

Granted, the Chinese already had been printing books with movable type since the 10th century, but since there are thousands of Chinese characters, the benefits of the technique was not as obvious as in European languages. With the invention of the Printing Press in Europe, it became possible for works to be easily disseminated in languages other than Latin. Very soon, books start appearing in the vernacular, and this brought along new interpretations of the bible, as well as secular texts of poems and art. The Printing Press was the tool that basically paved the way to widespread dissemination of Ideas. Reading became the new social mores, and in the eyes of the ruling classes, a widespread malaise they had no control over. To think what this did to mass culture; to the human imagination and creativity. Keep calm and read on.

Moral implications of Moore’s law

Our record of great inventions continue and we soon have the Telegraph which made the spreading of Ideas exponentially faster. Move further ahead into 20th century and things start to escalate. In the 1940s we invent the transistor, which will laid the foundations for the Personal Computer which then leads to this incredible idea that we could network machines across the globe through telephone cables, giving birth to the Internet. And finally, in 1991, with the invention of the world wide web by Sir Tim Berners Lee, we finally make access to ideas and information, not only ubiquitous, but also instantaneous. A colossal shift.

In 1965, Intel co-founder Gorden E Moore postulated a law stating that the number of transistors on integrated circuits will double every 18 months, making chips increasingly smaller and more efficient. Today we are well on track to arrive at the year 2020, when the size of meaningful computational power is anticipated to become zero by volume.

What does that even mean? It means that if we stay going at this pace, computers will be so small that they’ll be completely invisible, but faster than anything we have today. This means that we are rapidly bridging the gap between our Ideas and the Tools that bring them to life. Our tools will soon cease to be visible extensions of our needs. Instead they will become a part of us. This is at once an incredibly exciting and incredibly terrifying prospect.

Imagine a world where there is no sensory distinction between an Idea and the Tool that brings that Idea to life? Fascinating prospect, but how will that change our natural faculties? What happens when the very tools that helped us ideate better slowly stop us from thinking at all? When we no longer have the need to remember – thanks to the few extra gigs of memory plugged straight into your brain – won’t we forget to ask questions? What then comes of our moral compass?

![]()

![]()

When we become programmed by our tools, when we stop asking questions, we stop thinking for ourselves. And when we stop thinking for ourselves, we can be guaranteed that there will be someone else waiting to do the thinking for us.

Pixar created a brilliant depiction of this languid utopia where all the decisions have been made for you. This is the vision of the future where we have become programmed to accept information as it is fed to us. Where someone else is making all the decisions for us. Where we are no longer able to think critically. Sounds more or less like the present, doesn’t it?

The role of Art

So, what are the questions we must ask ourselves at the the onset of inventing new Tools? And at the onset of learning to use these tools? It is important to concern ourselves with these questions. And as such, these are the queries that are at the core of most art. Art is about posing the uncomfortable questions that society is too busy to concern itself with. I’d like to share a story of one such quandary that I faced, during an art project I did a couple of years ago.

I’m a designer by trade and after years of working in the digital world, I started feeling as though the digital tools that I was so excited about, these tools that I was using to do all this “creative” work, these tools had somehow started to use me. Sounds like science fiction, but I was steadily becoming part and parcel with the technology I was utilizing. I was turning into a cog in the machine, injecting that slightest dose of humanity that was needed in an otherwise technical phenomenon. I had a very basic function, compared to the larger machine, the larger vision, a vision that I had had little to do with.

And that was enough to make me pause. I realized that I wasn’t really using these tools in ways that were particularly meaningful. I saved up, took a sabbatical from work, and came up with a simple idea dubbed the Uniform Project that put to use all of the tools that I had been using everyday, but for an entirely different purpose. It was a self-imposed “wear one dress for one year” challenge I gave myself that was also designed to be a fundraiser for a cause that I cared about. I documented the challenge daily on a website that I designed, where people could follow the dailies, comment, donate and be part of this journey. What started with just friends as followers eventually turned into tens of thousands of supporters. At the end of the year, we had raised over $100,000 supporting over 300 kids in school in India.

I was once giving a talk about the project and someone in the crowd asked me something very interesting:

![]()

I was in a real quandary. We’re talking about a million dollars. A million dollars for kids who had absolutely nothing. So even if it rubbed me the wrong way, wouldn’t it still be the right thing to do to just get them to donate the money?

On the other hand, if a multi-billion dollar corporation wanted to support my cause, why did they need the approbation in return? Shouldn’t they be giving it away anyway? And if I accept their offer, am I not perpetuating these band aid solutions that allow corporations to be absolved of their responsibilities by giving them some easy PR? Art is precisely about raising such questions. To me, the Uniform Project was a success not only because it was able to help with the cause, but because it stirred up so many of active dialogues.

In the end, Coca Cola didn’t call me, but other companies did. And one company in particular, did make sense for us to work with. Most of the accessories I was using to create my dailies were stuff I would buy second hand on eBay. Ebay got wind of the project and they ended up getting behind the project in a way that didn’t go against the integrity of what we were trying to do. They didn’t try to turn it onto the eBay project, instead they matched almost half of the public donations and helped us create a lot of awareness around what we were trying to do.

What I’m getting at is this: In anything you do that is of any value, you will find yourself faced with some very hard questions. The tools that you use to mobilize your ideas and give them life, aren’t going to be able to answer these questions for you. Only you are.

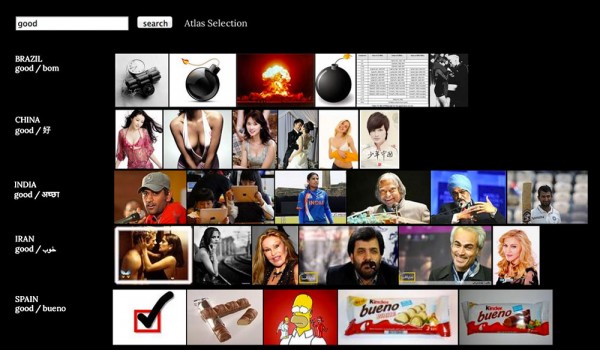

Image Atlas

I’d like to close with another project that grapples with the idea questioning our perceptions and presumptions. This is an art project created at a Rhizome hackathon by the late Aaron Swartz in collaboration with artist Taryn Simon. Aaron was someone who was consciously and relentlessly fighting to keep access to ideas and information free and democratic. To use the technological advances of our time to help us all think a little bit more critically about the application of the tools and how they can be used for both good things – progressive things – AND, bad things – reactionary things.

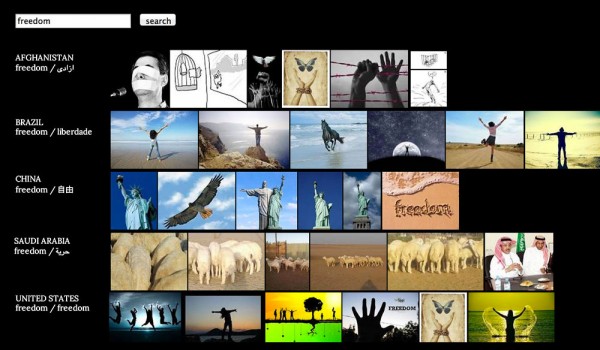

The project is called ImageAtlas and simply put, it is a different kind of search tool. You can type in any word or phrase into it, as you would in google, and it will give you image results for that search term, as it would be presented in different countries around the world across their local search engines. So this tool is basically aggregating image search results from various search engines and juxtaposing it next to each other. Let’s look at some examples.

SEARCH TERM: FREEDOM

Notice the contrast of imagery popping up for the word Freedom in Afghanistan versus Brazil. And apparently in Saudi Arabia, ‘freedom’ displays a herd of sheep. (The tool gives you a much wider list of countries, but I’ve just selected a few here to demonstrate how it works).

SEARCH TERM: AMERICA

Search result for “America” : It seems that in Afghanistan and Iran ‘America’ is a hypocritical liberty, or, Taylor Swift. Take your pick.

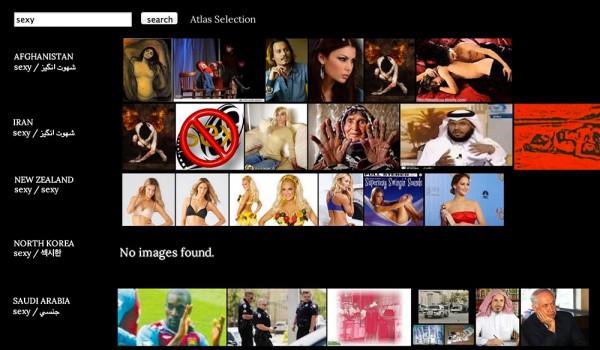

SEARCH TERM: SEXY

Search results for “Sexy” : No images found in North Korea.

SEARCH TERM: HELL

Search results for “Hell” : Apparently in Kenya, Microsoft is hell. In India it’s Demi Moore.

SEARCH TERM: GOOD

Search Results for “Good” : An interesting translation glitch in the program spits out images of bombs in brazil. (‘Good’ in portuguese is ‘bom’). In India Good is, of course, Cricket. And apparently in Spain it’s a Chocolate named Bueno and and ham named Homer simpson(^∇^)

So what Aaron’s trying to say is that the supposedly neutral tools like search engines that we’ve created, claim to present an unmediated view of the world through algorithms and stats and what have you – but these algorithms are programmed, programmable, and are in fact, programming us. The goal of this project was to expose some of the value judgments that get made when we look at images based on just what the search tool spits out.

We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.

In closing…

It took us centuries to agree on the idea of Zero. In the past our ancestors made one slow incremental step at a time towards the advancement of humanity. Today we’re starting to invent at the speed of light. And the tools that we invent, are taking on a life of their own. And as this happens, we must pause to ask how we will prepare for a world where technological progress is happening exponentially faster than social progress. How will we hold on to what makes us human when the tools we have created have become indistinguishable from us? How can we both embrace these new tools, but at the same time not become defined by them?

Real advancement, a meaningful change, the real revolution, is not going to come about by simply inventing smaller chips and faster gadgets. Today’s digital tools, like all tools, in and of itself, are neither good nor bad. They don’t possess any magical capacity for change. But they have the ability to empower anyone who uses them. It is not the tools themselves, but it is in the applications of these tools that our humanity can shine through.

Thank you.